Will we recover the freedoms we surrender to the fight against COVID-19?

The following text was published as an Op-Ed in the Globe and Mail (“We are giving up our freedoms in the fight against COVID-19. The question is will we get them back?”) on April 25, 2020

By Philip Slayton

Can we afford to be free?

Does freedom – a true freedom of strong precepts rather than meaningless platitudes – interfere with what we must do to survive? And, if it does, how much freedom will we surrender to remain alive, free from disease, adequately fed and suitably housed? All of it? Some of it? None of it?

In the time that follows the pandemic we will face choices that seem irrelevant in the fever of emergency. Should we be able to travel internationally as we wish? Can the police turn us back at provincial borders? Are we free to move, as the spirit takes us, within our cities? Can the government order us to stay at home? Can the government limit the right of assembly? Can businesses be closed by fiat? Can the government control prices and requisition goods? Do we need a larger military with a bigger role? Do we have to tell a policeman on demand who we are, where we are going and why? (As I walked through a familiar, now deserted, public plaza in downtown Toronto a few days ago I came across a new sign that said, “Have personal identification ready.”) Should the whereabouts of citizens be tracked by dramatically enhanced and mandatory surveillance technology? Should the government have the power to decide who lives and who dies through the allocation of limited medical resources?

Politicians seldom give up extreme executive power once they have it. Click To Tweet

In the liberal democracies, as the COVID-19 juggernaut flattens everything in its path, it is suddenly the time of the Strong Man, the political leader who juts out his jaw and proclaims to frightened and grateful followers that he will do what has to be done and whatever it takes. He tells us that big government and a state-run economy will save and protect us all, now and for the indefinite future. If we have to forget freedom, so be it. It’s worth it to stay alive with a roof over our head and a full belly.

Politicians seldom give up extreme executive power once they have it. They seldom leave the throne and go back to their cottage in the country to live in obscurity and cultivate their garden. Cincinnatus, the Roman dictator, is said to have relinquished absolute power and returned to working the plow at his small farm after beating back a foreign invasion, but that was two-and-a-half thousand years ago and the famous story is probably apocryphal. And even if a leader retreats – say, to the town of Crawford in the state of Texas – he generally leaves much unpleasantness behind. Draconian provisions to meet an emergency situation seldom have a sunset clause and strangely stay in place long after the emergency has passed. The Twin Towers were destroyed in 2001, but the Patriot Act and the Department of Homeland Security, and the fears and beliefs that fuelled them, are with the United States still. Income tax was introduced in Canada in 1917 as a temporary measure to help finance the First World War. “I have placed no time limit upon this measure … a year or two after the war is over, the measure should be reviewed,” said Sir Thomas White, then-Minister of Finance.

Surely modern Canada is different. Ours is a gentle, democratic land, a land of rights and freedoms, a country not given to overreaction or excess. Many of us easily assume our freedom is not in jeopardy. We are not Viktor Orban’s Hungary, or Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey, lurching toward dictatorship, or even Donald Trump’s turbulent and angry United States. Here at home, things will settle down. They will go back to the way they were. Well, maybe not quite the way they were, but something similar. We will stay a free society.

The structure of Canadian government has long permitted an excess of executive power and the country’s habit of deference to authority encourages its use. Click To Tweet

But this confidence is misplaced. It ignores dangers that lie all around us. Some of these dangers are not new. The structure of Canadian government has long permitted an excess of executive power and the country’s habit of deference to authority encourages its use. Some of these dangers are new, created by the catastrophic moment. There is a desire, born of fear and apprehension, to grant government new powers, to centralize authority in the federal government, to do away with confusing and contradictory provincial standards, to further empower the bureaucracy, to downplay the role of the legislative branch (a branch of government that to some seems increasingly a luxury), to ensure that civil liberties do not get in the way of decisive action. Will we see dramatically increased use of the notwithstanding clause in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms? What will happen to freedom of peaceful assembly, mobility rights, and our right not to be arbitrarily detained or imprisoned?

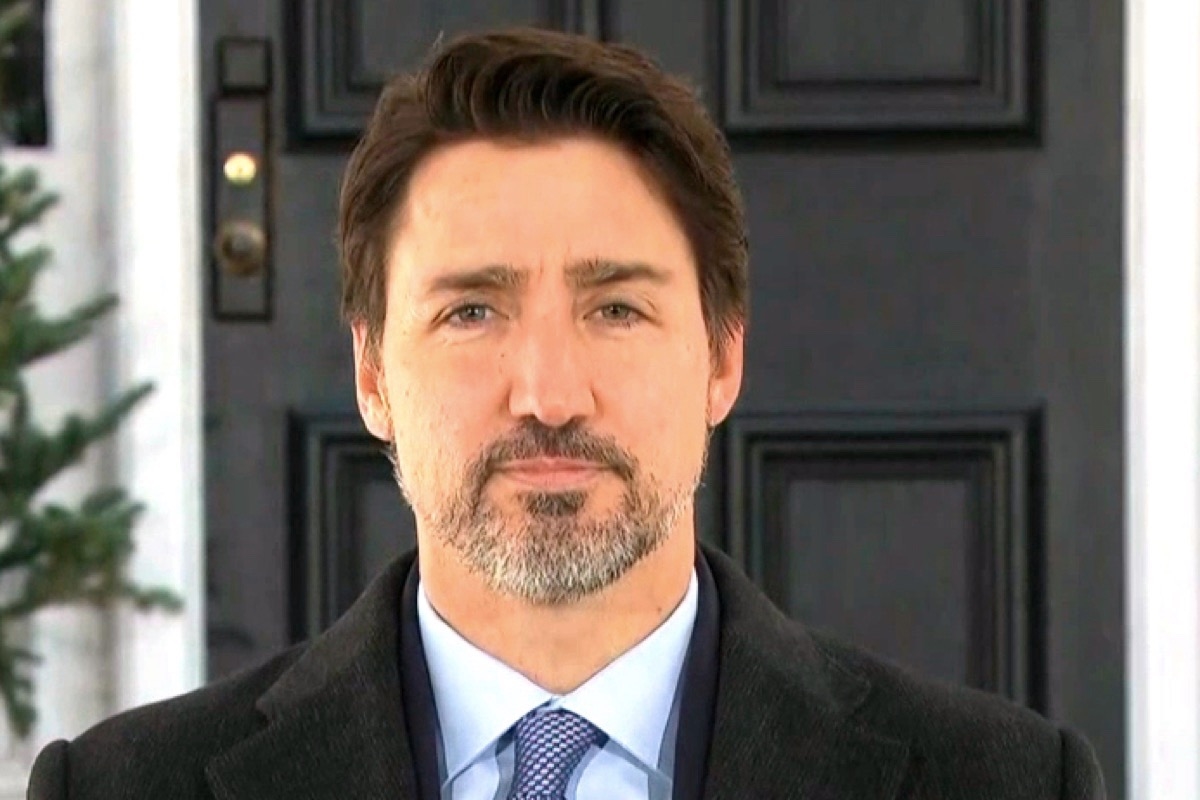

The Canadian prime minister is sometimes described as the most powerful political executive in the world. Just last year, The Globe and Mail’s Doug Saunders wrote, “The Prime Minister and his staff are not just an important part of the government; for all intents and purposes, they are the government.” The executive branch cannot always be trusted to exercise its huge power honestly and wisely. For example, the 2015 Liberal Party campaign platform said, “We are committed to ensuring that 2015 will be the last federal election conducted under the first-past-the-post voting system.” At the beginning of 2017, shortly after an all-party Commons committee proposed a proportional system of representation, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau decided his heartfelt promise of reform was politically inconvenient and abandoned it. In the 2015 election campaign, Mr. Trudeau specifically rejected the use of omnibus legislation, vast bills often with controversial measures buried deep inside to deflect debate and controversy. And yet, once in power, omnibus legislation became an accepted Liberal technique. Bill C-74 in 2018, for example, was described by the government as a “routine” budget implementation bill, but buried in its more than 500 pages were controversial carbon-pricing provisions and an amendment to the Criminal Code providing for deferred prosecution agreements (does anyone remember the SNC-Lavalin affair?). An egregious recent example of devil-may-care exercise of executive power was the attempt in COVID-19 emergency legislation (Bill C-13), without any discussion or publicity, to give the cabinet the ability until December, 2021, to raise taxes and spend money without Parliament’s approval. This proposal was withdrawn when opposition politicians and journalists cottoned on to it.

The punch of executive power in Canada is magnified by the deference to authority of the Canadian people. Canadians, unlike many Americans and Europeans, have not lost trust in experts, technocrats and bureaucrats. The Canadian core identity includes allegiance and submissiveness to institutions. Politeness and courtesy are considered important Canadian attributes. There is a deep-seated reluctance to challenge authority and a desire to avoid conflict. These are qualities that can promote social and political stability and they have earned the gratifying respect and even admiration of some around the world. But in our current circumstances, excessive deference is dangerous. It makes us too pliant and quiescent about what is done in our name. It encourages us to look the other way as we are systematically deprived of our liberty.

“Triage” is a word of the moment. It refers to the process of determining the most important people or things from among many that require attention. Triage is not just about the difficult decisions that must be made by ICU physicians. It applies also to fundamental choices that now must be made by Canadian society and societies around the world. Three important things compete for our attention: public health, the economy and freedom. We cannot apply equal attention and resources to each. No one would dispute that public health at the moment is the supreme concern. No one would dispute that the economy comes next. Is any attention left over for freedom? Not at the moment, when we are worried about ventilators and unemployment. We can worry about freedom later.

In a 2015 speech about climate change, Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of Canada and then the Bank of England, referred to the “tragedy of the horizon.” This is the penchant for being consumed by the present and discounting the future. It’s not just climate change that is subject to this tragedy. The COVID-19 pandemic presents a similar trap. Faced with a huge and immediately dangerous worldwide medical crisis, it seems necessary to respond forcefully, to do what has to be done, to have what Mr. Trudeau, using the language of wartime, calls a “civic mobilization.”

But what lies over the horizon? Will freedom be waiting for us there?

Philip Slayton is a former president of PEN Canada. His books include Mighty Judgment: How The Supreme Court of Canada Runs Your Life and the forthcoming Nothing Left to Lose: An Impolite Report on the State of Freedom in Canada, which is now available for pre-order.